Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the ovaries is a powerful, non-invasive imaging technique that provides detailed pictures of the pelvic organs. It plays a critical role in detecting, characterising, and staging ovarian tumours, especially when cancer is suspected. MRI offers greater soft tissue contrast than ultrasound or computed tomography (CT), making it especially useful when ovarian masses are complex or ambiguous.

An ovarian MRI might be recommended for several reasons:

Here are a few tips to help you prepare for your MRI8:

You can read more about preparation for Ezra’s MRI Scan with Spine here.

Upon arrival for your MRI, you will need to check in and complete a screening form. This will allow you to confirm the presence of implants, allergies, and whether you might need any anxiety medication.

During the scan, you will lie down on a sliding table. A dedicated surface or phased-array coil is typically placed over the limb or region of interest9. Your head will be nestled in a small cushion that will keep you still. The scan typically lasts 30-45 minutes of actual “table time”, during which the technician may acquire multiple sequences (settings). Expect loud knocking noises (up to 110 dB); earplugs or headphones are provided to reduce discomfort. It’s normal to feel mild table vibrations.

You’ll stay in touch with the team via a two-way intercom and a squeeze bulb, allowing you to communicate or pause the scan if needed. If contrast is required, it’s injected halfway through, possibly causing a brief cool sensation. After the final sequence, the coil is removed, and you’re free to go.

At Ezra, our MRI Scan with Spine scan takes around 60 minutes total, with 45 minutes of table time. Earplugs or headphones are available.

After the scan, you will be contacted by a medical provider working with Ezra within roughly a week. On the day of the appointment, you will receive a copy of your report and access to your scanned images through the online portal.

MRI is generally considered very safe when proper screening and protocols are followed, but certain risks and side effects should be understood:

A deeper dive into possible side effects (such as heat, headaches, and gadolinium deposition) is available in our full guide.

At Ezra, we employ a contrast-free approach using wide-bore T3 machines to deliver a comfortable scanning experience.

MRI reports of the ovary include specific terms that help clinicians assess the nature of a lesion or condition. Some common terms (and their meaning) include:

Complex Cyst: A “complex cyst” is a fluid-filled structure that is not completely simple; it may have internal septations (walls), debris, or small solid areas instead of being a thin-walled, clear fluid bubble16. Complex cysts are still often benign (e.g., haemorrhagic cyst, endometrioma, benign cystadenoma), but because they show more than just clear fluid, they usually need closer follow-up or further characterisation and sometimes surgery, depending on age, size, and other features.

Papillary Projections: These are small, finger-like or frond-like growths sticking out from the cyst wall or internal septations into the cyst cavity17. These are considered a type of “solid tissue” within a cyst, and the more or larger papillary projections present (especially if they enhance with contrast), the higher the concern for borderline tumour or invasive ovarian cancer rather than a purely benign cyst.

Restricted diffusion: This refers to tissue that looks bright on diffusion-weighted images and dark on the corresponding ADC map, suggesting tightly packed cells and limited water movement18. This pattern is often seen in malignant tumours, so restricted diffusion within a solid component or papillary area raises suspicion, although some benign lesions can occasionally show similar behaviour19.

Enhancement: “Enhancement” means that a structure takes up contrast dye and becomes brighter after injection, indicating blood flow20. When solid areas, nodules, or papillary projections within an adnexal mass enhance (especially more than the outer myometrium or more than expected for benign tissue), this supports the idea that they are living solid tissue rather than simple debris or cloth, and increases concern for neoplasm.

Thick Septations: Septations are internal walls that divide a cyst into compartments; “thick septations” means these walls are appreciably thicker rather than hairline thin21. Thin septations can be seen in benign multilocular cysts, but irregular or thick septations, particularly if they enhance after contrast, push the lesion into a higher-risk category and often prompt surgical evaluation.

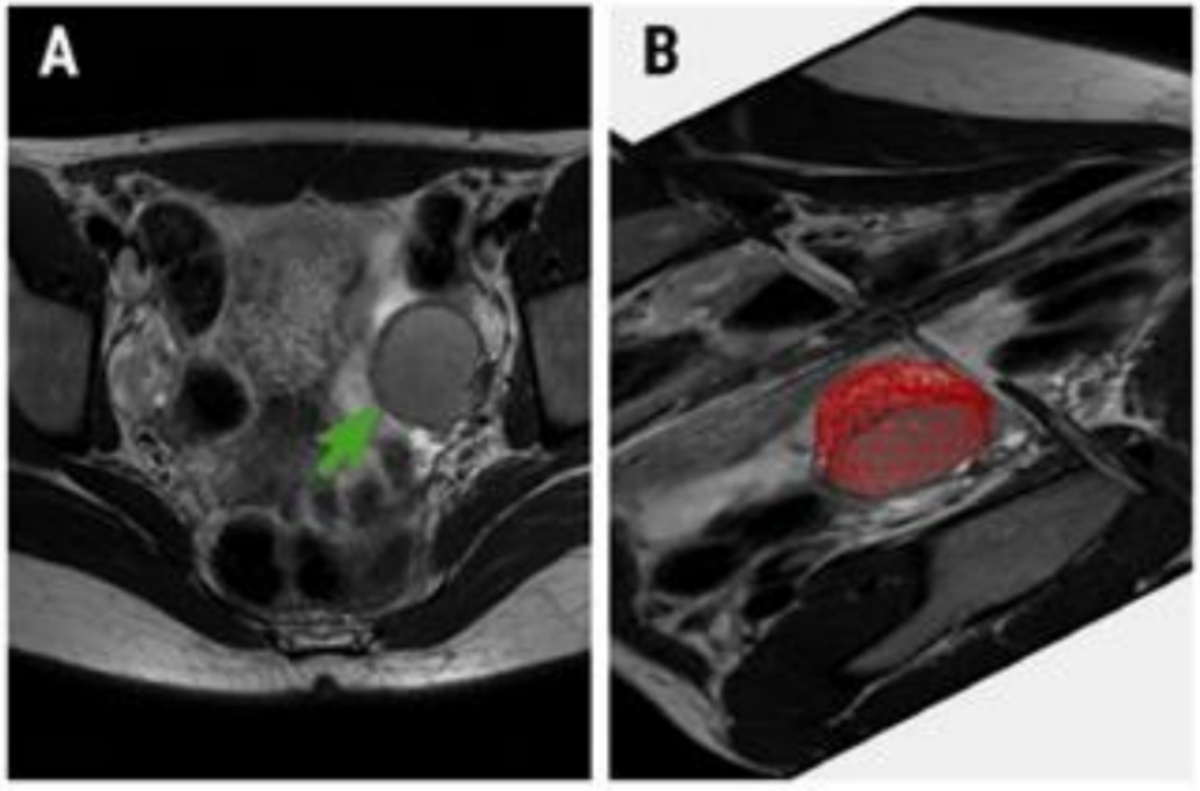

Solid Component: A “solid component” is any part of the lesion that is made of tissue rather than fluid, such as a mural nodule, papillary formation, irregular thickened wall, or a larger solid mass within or alongside a cyst22. The presence, size, and behaviour of solid components (enhancement, restricted diffusion, irregular margins) are key drivers in risk scores such as O-RADS MRI; more and more suspicious solid tissue generally means a higher probability that the mass could be malignant or borderline.

After the MRI scan, you will be free to go home and continue with your day without any precautions23. If you received a sedative, you will need another person to pick you up. You will also not be able to drive, consume alcohol, or operate heavy machinery 24 hours after the sedative.

A team of experts will review your results and determine whether a follow-up is necessary and recommend the appropriate treatment if needed. If abnormalities are found, you may undergo ongoing monitoring every 2-3 months to track recurrence. You can receive support in the form of counselling and advice on how to handle aspects like claustrophobia.

If you have a scan with us here at Ezra, you will receive your report within five to seven days and have the option to discuss it with a medical practitioner. You can also access your scan images through the online portal.

MRI can provide comprehensive information about ovarian cancer, aiding diagnosis, staging, and treatment monitoring.

MRI can often suggest whether a mass most likely arises from the ovary, fallopian tube, or peritoneum based on its attachment, how it displaces nearby organs, and which structures it appears to arise from24. It can also hint at tumour subtype (e.g., mucinous, serous, endometriosis-related) by the pattern of cysts, solid areas, fat, or blood, but final typing still relies on pathology.

MRI measures the maximum tumour diameter and can show precisely which ovary (or tube) is involved and how the mass relates to the uterus, bladder, rectum, and pelvic sidewalls1. This helps surgeons plan the incision, anticipate the difficulty of removal, and decide whether fertility-sparing surgery could be possible.

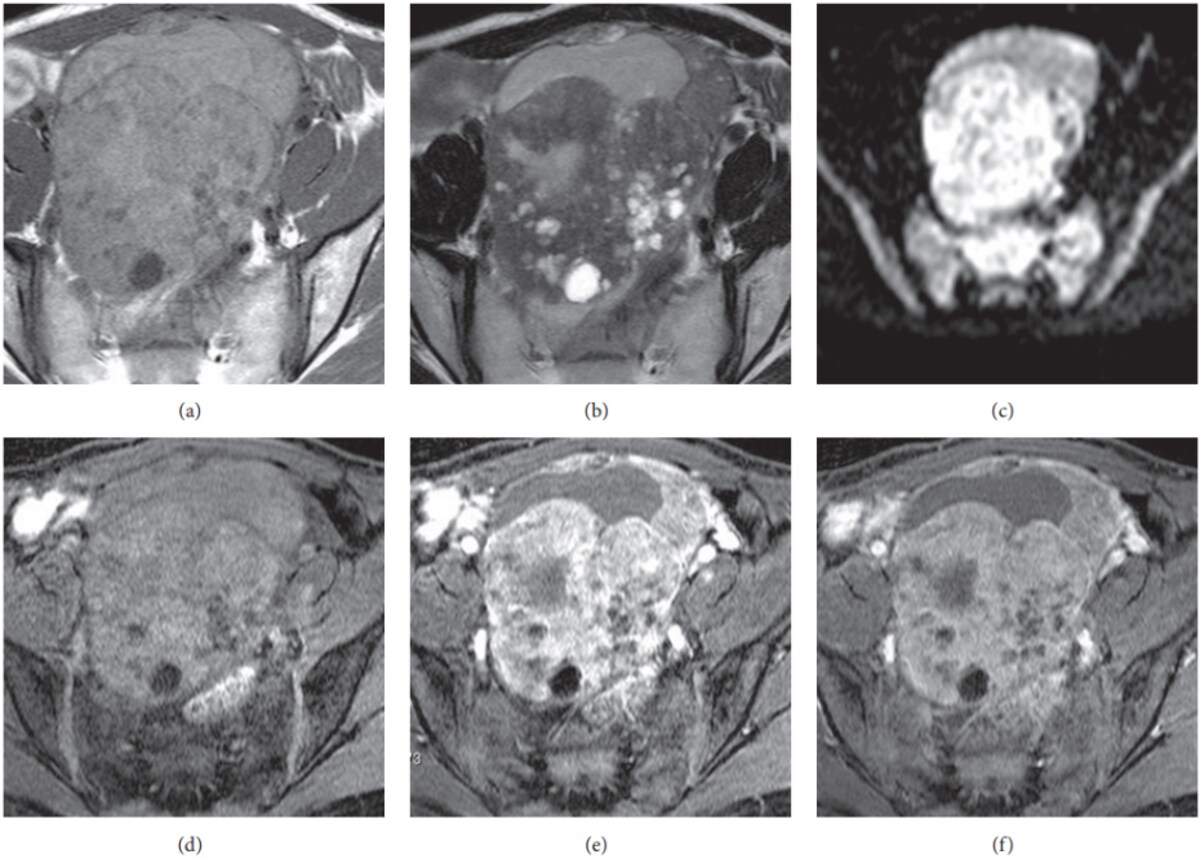

MRI clearly distinguishes fluid from solid tissue, showing whether a mass is mainly cystic, mainly solid, or mixed, and whether there are papillary projections, thick septa, or necrosis that raise concern for malignancy. Dynamic contrast and diffusion-weighted sequences further separate benign-appearing cysts from more suspicious, highly vascular, or diffusion-restricted solid components25.

MRI can show whether a tumour has invaded nearby organs (uterus, vagina, bladder, rectum) or the pelvic sidewall, and can depict peritoneal or omental deposits and implants on the serosal surfaces26. This information feeds into FIGO staging and helps determine whether optimal cytoreductive surgery is feasible.

MRI can detect enlarged pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes and describe their size, shape, and internal signal, which may suggest metastatic involvement, though small-volume nodal disease can still be missed27. MRI findings are often interpreted alongside other imaging and clinical data.

MRI is sensitive to free fluid and can show ascites, loculated collections, and fluid tracking in the abdomen and pelvis, which are common in advanced ovarian cancer28. The presence and volume of ascites, especially with peritoneal nodules, support a diagnosis of malignant spread and influence both staging and symptom management decisions.

Ezra provides a radiologist-reviewed report in a non-technical and easy-to-understand format on your dashboard.

MRI can often suggest what type of ovarian tumour is present by its internal contents (fluid, blood, fat, solid tissue), signal pattern, and enhancement.

These cancers usually look like a bulky “lump and cyst” mixed mass rather than a simple, thin-walled cyst. The walls can be thick and uneven, with little lumps or fronds growing inside, and the solid parts light up strongly after contrast, which tells doctors the tissue is very active29. Cancer of this type often comes with extra fluid in the tummy (ascites) and tiny deposits on the lining of the abdomen, and it may affect both ovaries, all of which increase suspicion for invasive epithelial carcinoma rather than a benign cyst.

Borderline tumours often look like bunches of connected cysts with a more tidy, organised structure. They can have papillary projections or small solid areas that still take up contrast, but they usually cause less fluid in the abdomen and less obvious spread than full-blown cancer30. On MRI, they often sit in the “in-between” zone: more worrying than a simple cyst, but not as aggressive-looking as invasive carcinoma.

Endometriomas are “blood-filled cysts” related to endometriosis, sometimes called “chocolate cysts”. On MRI, the blood inside makes them look very bright in some pictures and darker in others, in a pattern that is quite characteristic31. They usually do not have suspicious solid lumps inside; if a new or growing solid nodule appears in the wall and takes up contrast, that can be a warning sign that a cancer is developing inside an endometrioma and needs closer assessment.

Dermoids are benign tumours that can contain fat, hair, and sometimes teeth or bone. The fat makes them stand out on MRI, so radiologists can often recognise them easily31. They often look like a mix of fluid and fatty material, sometimes with a more solid “plug” (a Rokitansky nodule). Most are harmless, but if a new, irregular solid area grows inside and enhances with contrast, doctors may worry about the rare chance of a cancer forming within a dermoid.

H3: Fibroma (and fibro-thecoma)

Fibromas are solid, firm ovarian tumours made mostly of fibrous tissue (a bit like a rubbery scar). On MRI, they tend to look very dark on the fluid-sensitive images compared with many other ovarian tumours, which helps radiologists recognise them33. They usually take up contrast slowly and less strongly than cancers. They can sometimes cause fluid in the abdomen and a pleural effusion (Meigs syndrome), but their very dark appearance on MRI often points toward a benign fibrous tumour rather than a malignant one.

Ezra screens for over 500 conditions, including the brain.

MRI for ovarian cancer uses a set of sequences that each answer a different question about the mass.

T1‑weighted images are good at showing fat and blood‑containing material as bright, and simple fluid as darker, which helps identify fat‑containing tumours (such as dermoids) and blood‑filled cysts (such as endometriomas)34.

T2-weighted images make fluid appear bright and dense fibrous tissue appear darker, which helps show the overall shape and internal structure of an ovarian mass35. Radiologists use T2 to assess how many cystic spaces there are, how thick the walls and septa are, and whether there are internal solid nodules or papillary projections.

DWI assesses how water molecules move within tissues. Tumours tend to restrict water movement, so they stand out as areas of restricted diffusion36–38. This helps in identifying and confirming suspicious lesions, even when they are small or subtle.

This is a map derived from DWI that provides a numerical value to help separate aggressive cancers (which have lower ADC values) from less aggressive tumours. Lower ADC suggests increased tumour cell density36,37.

DCE captures images over time after a contrast dye is injected. Malignant tumours often soak up the dye earlier than normal bladder wall tissue, a sign of abnormal blood vessels36,37,39. This helps distinguish cancer from benign tissue and is useful for staging and treatment monitoring.

Ezra’s MRI Scan with Spine costs £2,395 and is currently available at their partner clinic in Marylebone, London, and in Sidcup, with more locations planned in the future. No referral is required, so you can book your scan directly without consulting a GP or specialist first. Most people pay out-of-pocket, as insurance typically does not cover self-referred scans, but you may be able to seek reimbursement depending on your policy.

Yes, for complex or suspicious cases.

No, it is painless, but it can be noisy and requires you to be still for a period of time.

Often, yes, but you should disclose all devices to your radiologist.

1. Sohaib SAA, Reznek RH. MR imaging in ovarian cancer. Cancer Imaging. 2007;7(Special issue A):S119-S129. doi:10.1102/1470-7330.2007.9046

2. Yeoh M. Investigation and management of an ovarian mass. Australian Family Physician. 2015;44(1). Accessed December 3, 2025. https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2015/january-february/investigation-and-management-of-an-ovarian-mass

3. Charkhchi P, Cybulski C, Gronwald J, Wong FO, Narod SA, Akbari MR. CA125 and Ovarian Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(12):3730. doi:10.3390/cancers12123730

4. Screening for ovarian cancer. Accessed December 3, 2025. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/ovarian-cancer/getting-diagnosed/screening

5. Ovarian Cancer Stages | Staging for Ovarian Cancer. Accessed December 3, 2025. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/ovarian-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/staging.html

6. Radiology (ACR) RS of NA (RSNA) and AC of. Staging and Follow-up of Ovarian Cancer. Radiologyinfo.org. Accessed December 3, 2025. https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/acs-staging-ovarian-cancer

7. Sahin H, Akdogan AI, Smith J, Zawaideh JP, Addley H. Serous borderline ovarian tumours: an extensive review on MR imaging features. Br J Radiol. 2021;94(1125):20210116. doi:10.1259/bjr.20210116

8. Radiology (ACR) RS of NA (RSNA) and AC of. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) - Head. Radiologyinfo.org. Accessed July 3, 2025. https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/mri-brain

9. Gruber B, Froeling M, Leiner T, Klomp DWJ. RF coils: A practical guide for nonphysicists. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;48(3):590-604. doi:10.1002/jmri.26187

10. Gill A, Shellock FG. Assessment of MRI issues at 3-Tesla for metallic surgical implants: findings applied to 61 additional skin closure staples and vessel ligation clips. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2012;14(1):3. doi:10.1186/1532-429X-14-3

11. Potential Hazards and Risks. UCSF Radiology. January 20, 2016. Accessed March 14, 2025. https://radiology.ucsf.edu/patient-care/patient-safety/mri/potential-hazards-risks

12. Costello JR, Kalb B, Martin DR. Incidence and Risk Factors for Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agent Immediate Reactions. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;25(6):257-263. doi:10.1097/RMR.0000000000000109

13. McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF, et al. Gadolinium Deposition in Human Brain Tissues after Contrast-enhanced MR Imaging in Adult Patients without Intracranial Abnormalities. Radiology. 2017;285(2):546-554. doi:10.1148/radiol.2017161595

14. Mansour S, Hamed S, Kamal R. Spectrum of Ovarian Incidentalomas: Diagnosis and Management. Br J Radiol. 2023;96(1142):20211325. doi:10.1259/bjr.20211325

15. Mall MA, Stahl M, Graeber SY, Sommerburg O, Kauczor HU, Wielpütz MO. Early detection and sensitive monitoring of CF lung disease: Prospects of improved and safer imaging. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2016;51(S44):S49-S60. doi:10.1002/ppul.23537

16. Hartge P, Hayes R, Reding D, et al. Complex ovarian cysts in postmenopausal women are not associated with ovarian cancer risk factors: preliminary data from the prostate, lung, colon, and ovarian cancer screening trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(5):1232-1237. doi:10.1067/mob.2000.107401

17. Valentin L, Ameye L, Savelli L, et al. Unilocular adnexal cysts with papillary projections but no other solid components: is there a diagnostic method that can classify them reliably as benign or malignant before surgery? Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;41(5):570-581. doi:10.1002/uog.12294

18. Addley H, Moyle P, Freeman S. Diffusion-weighted imaging in gynaecological malignancy. Clinical Radiology. 2017;72(11):981-990. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2017.07.014

19. Agostinho L, Horta M, Salvador JC, Cunha TM. Benign ovarian lesions with restricted diffusion. Radiol Bras. 2019;52(2):106-111. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2018.0078

20. Contrast enhancement | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org. Accessed December 3, 2025. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/contrast-enhancement?lang=gb

21. The Radiology Assistant : Roadmap to evaluate ovarian cysts. Accessed December 3, 2025. https://radiologyassistant.nl/abdomen/unsorted/roadmap-to-evaluate-ovarian-cysts

22. Sadowski EA, Maturen KE, Rockall A, et al. Ovary: MRI characterisation and O-RADS MRI. Br J Radiol. 2021;94(1125):20210157. doi:10.1259/bjr.20210157

23. MRI scan. NHS inform. Accessed July 3, 2025. https://www.nhsinform.scot/tests-and-treatments/scans-and-x-rays/mri-scan/

24. Engbersen MP, Van Driel W, Lambregts D, Lahaye M. The role of CT, PET-CT, and MRI in ovarian cancer. Br J Radiol. 2021;94(1125):20210117. doi:10.1259/bjr.20210117

25. Wasnik AP, Menias CO, Platt JF, Lalchandani UR, Bedi DG, Elsayes KM. Multimodality imaging of ovarian cystic lesions: Review with an imaging based algorithmic approach. World J Radiol. 2013;5(3):113-125. doi:10.4329/wjr.v5.i3.113

26. Nougaret S, Nikolovski I, Paroder V, et al. MRI of Tumors and Tumor Mimics in the Female Pelvis: Anatomic Pelvic Space–based Approach. Radiographics. 2019;39(4):1205-1229. doi:10.1148/rg.2019180173

27. Dezen T, Rossini RR, Spadin MD, et al. Accuracy of MRI for diagnosing pelvic and para‑aortic lymph node metastasis in cervical cancer. Oncol Rep. 2021;45(6):100. doi:10.3892/or.2021.8051

28. Wall SD, Hricak H, Bailey GD, Kerlan RK, Goldberg HI, Higgins CB. MR imaging of pathologic abdominal fluid collections. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1986;10(5):746-750. doi:10.1097/00004728-198609000-00006

29. Ohya A, Fujinaga Y. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of cystic ovarian tumors: major differential diagnoses in five types frequently encountered in daily clinical practice. Jpn J Radiol. 2022;40(12):1213-1234. doi:10.1007/s11604-022-01321-x

30. Naqvi J, Nagaraju E, Ahmad S. MRI appearances of pure epithelial papillary serous borderline ovarian tumours. Clin Radiol. 2015;70(4):424-432. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2014.11.005

31. Salman S, Shireen N, Riyaz R, Khan SA, Singh JP, Uttam A. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of gynecological mass lesions: A comprehensive analysis with histopathological correlation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(32):e39312. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000039312

32. Lupean RA, Ștefan PA, Csutak C, et al. Differentiation of Endometriomas from Ovarian Hemorrhagic Cysts at Magnetic Resonance: The Role of Texture Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(10):487. doi:10.3390/medicina56100487

33. Bouab M, Touimi AB, El Omri H, Boufettal H, Mahdaoui S, Samouh N. Primary ovarian fibroma in a postmenopausal woman: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;92:106842. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.106842

34. Peyrot H, Montoriol PF, Canis M. Spontaneous T1-Hyperintensity Within an Ovarian Lesion: Spectrum of Diagnoses. Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal. 2015;66(2):115-120. doi:10.1016/j.carj.2014.07.006

35. Foti PV, Attinà G, Spadola S, et al. MR imaging of ovarian masses: classification and differential diagnosis. Insights Imaging. 2015;7(1):21-41. doi:10.1007/s13244-015-0455-4

36. Shalaby EA, Mohamed AR, Elkammash TH, Abouelkheir RT, Housseini AM. Role of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis and staging of urinary bladder cancer. Curr Urol. 2022;16(3):127-135. doi:10.1097/CU9.0000000000000128

37. Akin O, Lema-Dopico A, Paudyal R, et al. Multiparametric MRI in Era of Artificial Intelligence for Bladder Cancer Therapies. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(22):5468. doi:10.3390/cancers15225468

38. Carando R, Afferi L, Marra G, et al. The effectiveness of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in bladder cancer (Vesical Imaging-Reporting and Data System): A systematic review. Arab J Urol. 18(2):67-71. doi:10.1080/2090598X.2020.1733818

39. He K, Meng X, Wang Y, et al. Progress of Multiparameter Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Bladder Cancer: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Diagnostics. 2024;14(4):442. doi:10.3390/diagnostics14040442