A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the prostate uses strong magnets and radio waves to create detailed internal images of the prostate gland and surrounding tissues. In the setting of suspected prostate cancer, MRI helps in detection, localisation, staging (i.e., whether it has extended beyond the prostate), and in guiding further tests like biopsy. Often it is done as a “multi‑parametric” MRI (mpMRI), which combines multiple sequences for better accuracy.

A prostate MRI is used to get a detailed look at the prostate when other tests, like prostate-specific antigen (PSA) or digital rectal examination (DRE), raise concern or are inconclusive. It also helps decide whether you need a biopsy, where to target it, and how far any cancer may have spread.

Here are a few tips to help you prepare for your MRI5:

You can read more about preparation for Ezra’s MRI Scan with Spine here.

Upon arrival for your MRI, you will need to check in and complete a screening form. This will allow you to confirm the presence of implants, allergies, and whether you might need any anxiety medication.

During the scan, you will lie down on a sliding table. A dedicated surface or phased-array coil is typically placed over the limb or region of interest6. Your head will be nestled in a small cushion that will keep you still. The scan typically lasts 30-45 minutes of actual “table time”, during which the technician may acquire multiple sequences (settings). Expect loud knocking noises (up to 110 dB); earplugs or headphones are provided to reduce discomfort. It’s normal to feel mild table vibrations.

You’ll stay in touch with the team via a two-way intercom and a squeeze bulb, allowing you to communicate or pause the scan if needed. If contrast is required, it’s injected halfway through, possibly causing a brief cool sensation. After the final sequence, the coil is removed, and you’re free to go.

At Ezra, our MRI Scan with Spine scan takes around 60 minutes total, with 45 minutes of table time. Earplugs or headphones are available.

After the scan, you will be contacted by a medical provider working with Ezra within roughly a week. On the day of the appointment, you will receive a copy of your report and access to your scanned images through the online portal.

MRI is generally considered very safe when proper screening and protocols are followed, but certain risks and side effects should be understood:

A deeper dive into possible side effects (such as heat, headaches, and gadolinium deposition) is available in our full guide.

At Ezra, we employ a contrast-free approach using wide-bore T3 machines to deliver a comfortable scanning experience.

MRI reports of the prostate include specific terms that help clinicians assess the nature of a lesion or condition. Some common terms (and their meaning) include:

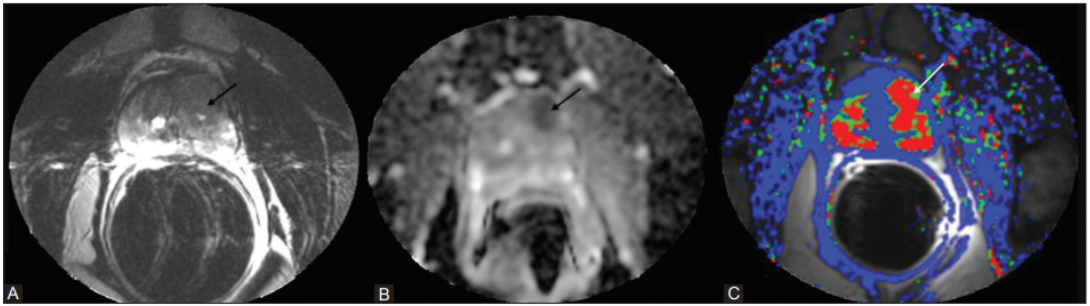

PI-RADS score (1-5): A standard scoring system that rates how likely it is that an area on MRI is a clinically significant prostate cancer: 1-2 = unlikely, 3 = uncertain, 4-5 = likely13.

ADC value/diffusion restriction: On diffusion-weighted imaging, cancer often appears as “restricted diffusion” with a low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), reflecting tightly packed cells14. Benign tissue usually has higher ADC values and less restriction15.

Extraprostatic extension (EPE): Means the tumour appears to extend through the outer capsule of the prostate into surrounding fat or structures, suggesting at least T3 disease on staging16.

Seminal vesicle invasion: Indicates spread of tumour into one or both seminal vesicles, which is a more advanced local stage and affects treatment planning and prognosis17.

Multifocal lesion: More than one suspicious focus of abnormal signal in the prostate, which is common in prostate cancer and can influence how biopsy and treatment are planned18.

Peripheral zone (PZ) vs. transition zone (TZ): This describes where the lesion sits: most cancers arise in the peripheral zone, whereas BPH mainly affects the transition zone19,20. Location changes how features are interpreted and how lesions are scored in PI-RADS.

After the MRI scan, you will be free to go home and continue with your day without any precautions21. If you received a sedative, you will need another person to pick you up. You will also not be able to drive, consume alcohol, or operate heavy machinery 24 hours after the sedative.

A team of experts will review your results and determine whether a follow-up is necessary and recommend the appropriate treatment if needed. If abnormalities are found, you may undergo ongoing monitoring every 2-3 months to track recurrence. You can receive support in the form of counselling and advice on how to handle aspects like claustrophobia.

If you have a scan with us here at Ezra, you will receive your report within five to seven days and have the option to discuss it with a medical practitioner. You can also access your scan images through the online portal.

MRI can show where prostate cancer is, how aggressive it looks, and whether it has started to spread just outside the gland, which all feed into biopsy decisions and treatment planning.

MRI can show suspicious lesions within the prostate, including their size, exact location (e.g., peripheral vs transition zone), shape, and number of foci. mpMRIs combine anatomical and functional sequences to characterise these lesions and help distinguish tumours from benign changes such as BPH or prostatitis22.

mpMRI can help estimate whether a lesion is likely to be clinically significant (higher-grade, higher-volume cancer) versus a low-risk, slow-growing disease that may be suitable for monitoring23. Scoring systems such as PI-RADS link MRI appearance to the probability of clinically significant cancer and guide whether biopsy is recommended or active surveillance is reasonable.

MRI can show whether the cancer appears confined within the prostate capsule or shows signs of extraprostatic extension, such as capsular bulging, breach, or neurovascular bundle involvement24. It can also depict seminal vesicle invasion and involvement of adjacent pelvic structures, which feeds into TNM staging and selection of surgery, radiotherapy fields, or multimodal treatment.

By mapping suspicious areas, MRI allows biopsies to be targeted to lesions rather than sampled “blind”, increasing detection of clinically significant cancers and reducing unnecessary cores25. When mpMRI shows no or only very low-suspicion lesions, the chance of significant cancer is lower, so some men can avoid or defer biopsy and continue PSA/DRE monitoring instead.

In men already diagnosed with low-risk cancer, MRI can provide additional reassurance that there is no hidden high-grade lesion, supporting decisions to pursue or continue active surveillance. Serial MRI can also be used alongside PSA and repeat biopsies to monitor for radiological progression that might trigger a shift from surveillance to active treatment.

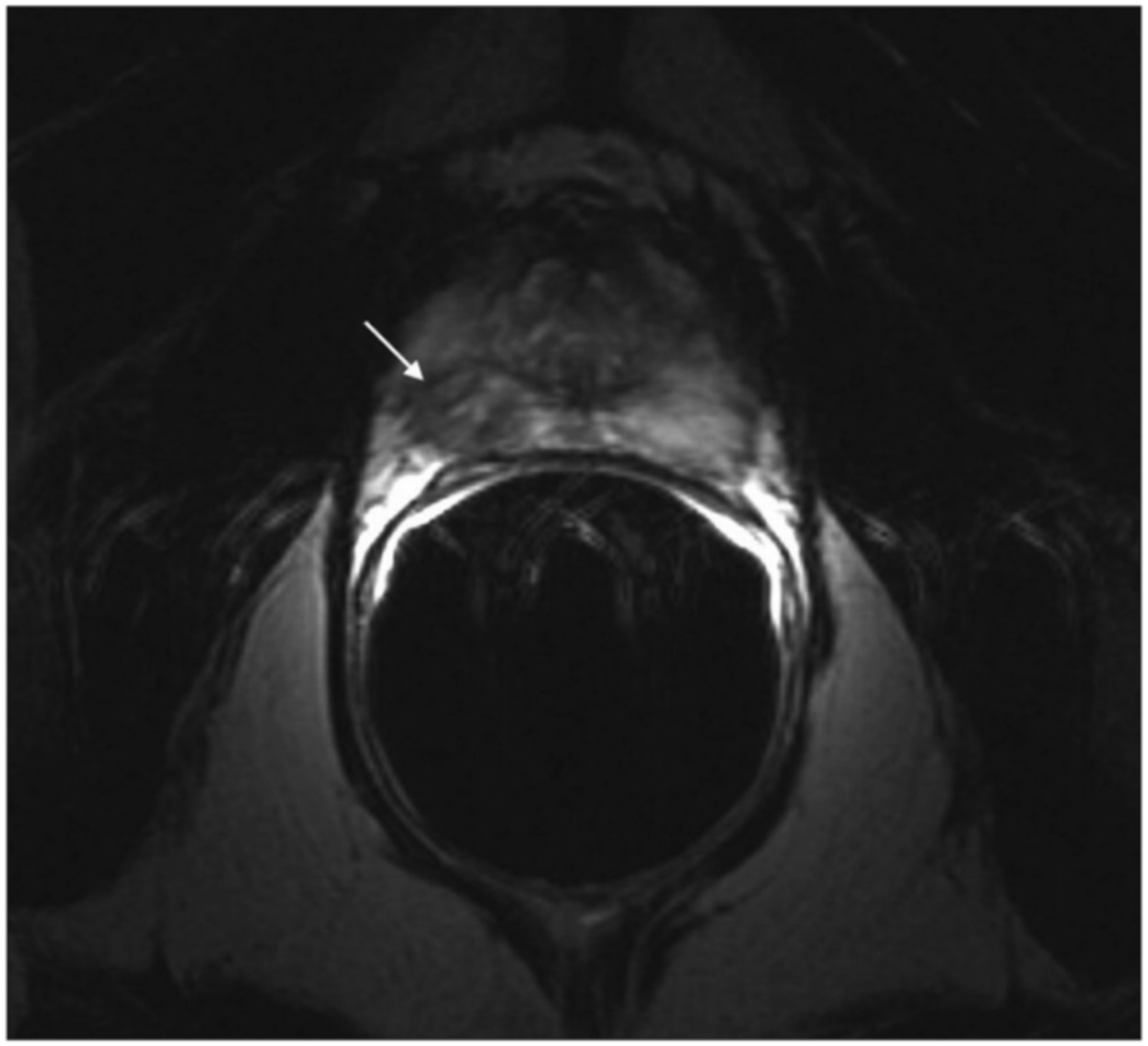

Most clinically important prostate tumours are adenocarcinomas. On MRI, they tend to be dark on T2, show restricted diffusion (low ADC), and often enhance early with contrast, but appearances vary by zone, grade, and size26.

Most prostate cancers are acinar adenocarcinomas arising in the peripheral zone; on mpMRI, these usually appear as focal, round or oval low-signal areas on T2-weighted images, with marked diffusion restriction and corresponding low ADC values27.

Transition zone cancers are also usually adenocarcinomas but are embedded within BPH Anodules, so they often look like ill-defined, lenticular, T2-dark areas with obscured margins, requiring closer attention to diffusion and enhancement patterns to separate them from benign nodules29.

Clinically significant cancers (higher grade, larger volume) tend to show more pronounced diffusion restriction, with very low ADC and very bright high-b-value DWI signal, and more conspicuous, early contrast uptake on dynamic imaging30. These lesions are more likely to be scored PI-RADS 4-5 and correlate with higher Gleason/ISUP grades on biopsy.

Low-grade, small-volume tumours may show only mild T2 hypointensity and modest diffusion changes, sometimes blending with background signal or benign changes such as inflammation31. Because of this overlap, MRI is less sensitive for indolent lesions, and some low-risk cancers are missed or reported as equivocal (e.g., PI-RADS 3), which is why biopsy and clinical context still matter for definitive diagnosis.

Ezra screens for over 500 conditions, including the brain.

MRI for prostate cancer uses a set of sequences that each answer a different question about the mass.

mpMRI combines at least three components: high-resolution T2-weighted images for anatomy, DWI/ADC for cell density, and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) imaging for vascularity32. This protocol is still the reference standard in many centres because it improves confidence in calling a lesion benign vs clinically significant, and it underpins PI-RADS.

bpMRI uses T2-weighted and DWI/ADC sequences but omits contrast, shortening scan time, avoiding gadolinium, and reducing cost33. Multiple comparative studies suggest bmMRI can approach mpMRI’s accuracy for detecting clinically significant cancer in pre-biopsy settings, though performance is reader- and centre-dependent, and some guidelines still default to mpMRI.

Older 1.5T protocols often used an endorectal coil to boost signal-to-noise and local staging detail, especially for extraprostatic extension and seminal vesicle invasion34. With modern 3T scanners and good pelvic phased-array coils, endorectal coils are now rarely needed, reserved mainly for specific research or re-staging scenarios.

A 3T scanner generally offers higher spatial resolution and better DWI quality than a 1.5T scanner, which can improve lesion conspicuity and PI-RADS assessment when combined with experienced reporting35. Advanced techniques like MR spectroscopy, elastography, or experimental quantitative mapping are mostly research-level or adjunctive rather than part of routine diagnostic pathways.

Ezra’s MRI Scan with Spine costs £2,395 and is currently available at their partner clinic in Marylebone, London, and in Sidcup, with more locations planned in the future. No referral is required, so you can book your scan directly without consulting a GP or specialist first. Most people pay out-of-pocket, as insurance typically does not cover self-referred scans, but you may be able to seek reimbursement depending on your policy.

Not always. If MRI shows no suspicious lesion (e.g., PI‑RADS 1‑2) and other risk factors are low, your doctor may recommend monitoring rather than immediate biopsy.

Yes. MRI is highly useful but not perfect. Some small or low‑grade cancers may not be visible. Also, MRI cannot reliably detect distant metastases beyond the pelvis.

You must inform the imaging centre. Some implants are MRI‑safe; others may need special protocols or alternative imaging.

No, the MRI itself is painless. You may feel discomfort from lying still or from the injection of contrast. The machine is noisy.

MRI helps identify whether cancer needs treatment (vs monitoring), helps guide the biopsy and helps with planning surgery or radiotherapy if needed (by showing the extent of disease).

1. Multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) scan for prostate cancer. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/tests-and-scans/multiparametric-mri

2. MRI scan. Prostate Cancer UK. Accessed December 4, 2025. http://prostatecanceruk.org/prostate-information-and-support/prostate-tests/mri-scan

3. Radiology (ACR) RS of NA (RSNA) and AC of. Ultrasound- and MRI-Guided Prostate Biopsy. Radiologyinfo.org. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/prostate-biopsy

4. Feger J. Seminal vesicle invasion | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org. Radiopaedia. doi:10.53347/rID-85200

5. Radiology (ACR) RS of NA (RSNA) and AC of. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) - Head. Radiologyinfo.org. Accessed July 3, 2025. https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/mri-brain

6. Gruber B, Froeling M, Leiner T, Klomp DWJ. RF coils: A practical guide for nonphysicists. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;48(3):590-604. doi:10.1002/jmri.26187

7. Gill A, Shellock FG. Assessment of MRI issues at 3-Tesla for metallic surgical implants: findings applied to 61 additional skin closure staples and vessel ligation clips. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2012;14(1):3. doi:10.1186/1532-429X-14-3

8. Potential Hazards and Risks. UCSF Radiology. January 20, 2016. Accessed March 14, 2025. https://radiology.ucsf.edu/patient-care/patient-safety/mri/potential-hazards-risks

9. Costello JR, Kalb B, Martin DR. Incidence and Risk Factors for Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agent Immediate Reactions. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;25(6):257-263. doi:10.1097/RMR.0000000000000109

10. McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF, et al. Gadolinium Deposition in Human Brain Tissues after Contrast-enhanced MR Imaging in Adult Patients without Intracranial Abnormalities. Radiology. 2017;285(2):546-554. doi:10.1148/radiol.2017161595

11. Sherrer RL, Lai WS, Thomas JV, Nix JW, Rais-Bahrami S. Incidental findings on multiparametric MRI performed for evaluation of prostate cancer. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43(3):696-701. doi:10.1007/s00261-017-1237-x

12. Mall MA, Stahl M, Graeber SY, Sommerburg O, Kauczor HU, Wielpütz MO. Early detection and sensitive monitoring of CF lung disease: Prospects of improved and safer imaging. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2016;51(S44):S49-S60. doi:10.1002/ppul.23537

13. Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/prostate-imaging-reporting-and-data-system-pi-rads-2?lang=gb

14. Turkbey B, Aras O, Karabulut N, et al. Diffusion weighted MRI for detecting and monitoring cancer: a review of current applications in body imaging. Diagn Interv Radiol. Published online 2011. doi:10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.4708-11.2

15. Pekcevik Y, Kahya MO, Kaya A. Characterization of Soft Tissue Tumors by Diffusion-Weighted Imaging. Iran J Radiol. 2015;12(3):e15478. doi:10.5812/iranjradiol.15478v2

16. Desai PK. Extraprostatic extension of prostate cancer | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org. Radiopaedia. doi:10.53347/rID-6049

17. Potter SR, Epstein JI, Partin AW. Seminal Vesicle Invasion by Prostate Cancer: Prognostic Significance and Therapeutic Implications. Rev Urol. 2000;2(3):190-195.

18. Matsumoto K, Akita H, Hashiguchi A, et al. Detection of the Highest-Grade Lesion in Multifocal Discordant Prostate Cancer by Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2024;22(3):102084. doi:10.1016/j.clgc.2024.102084

19. Ng M, Leslie SW, Baradhi KM. Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed September 3, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558920/

20. Prostate Cancer - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470550/

21. MRI scan. NHS inform. Accessed July 3, 2025. https://www.nhsinform.scot/tests-and-treatments/scans-and-x-rays/mri-scan/

22. Turkbey B, Choyke PL. Multiparametric MRI and prostate cancer diagnosis and risk stratification. Curr Opin Urol. 2012;22(4):310-315. doi:10.1097/MOU.0b013e32835481c2

23. Johnson LM, Turkbey B, Figg WD, Choyke PL. Multiparametric MRI in prostate cancer management. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(6):346-353. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.69

24. Guerra A, Flor-de-Lima B, Freire G, Lopes A, Cassis J. Radiologic-pathologic correlation of prostatic cancer extracapsular extension (ECE). Insights Imaging. 2023;14:88. doi:10.1186/s13244-023-01428-3

25. Drost FH, Osses DF, Nieboer D, et al. Prostate MRI, with or without MRI‐targeted biopsy, and systematic biopsy for detecting prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2019(4):CD012663. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012663.pub2

26. Yamada K, Kozawa N, Nagano H, Fujita M, Yamada K. MRI features of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the prostate: report of four cases. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44(4):1261-1268. doi:10.1007/s00261-019-01956-x

27. Laert J, França Santana T, Lupi Manso N. Penile Metastasis From Prostatic Adenocarcinoma: A Case Report. Cureus. 17(1):e77039. doi:10.7759/cureus.77039

28. Hedgire SS, Oei TN, Mcdermott S, Cao K, Patel M Z, Harisinghani MG. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of prostate cancer. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2012;22(3):160-169. doi:10.4103/0971-3026.107176

29. Akin O, Sala E, Moskowitz CS, et al. Transition zone prostate cancers: features, detection, localization, and staging at endorectal MR imaging. Radiology. 2006;239(3):784-792. doi:10.1148/radiol.2392050949

30. Jyoti R, Jain TP, Haxhimolla H, Liddell H, Barrett SE. Correlation of apparent diffusion coefficient ratio on 3.0 T MRI with prostate cancer Gleason score. Eur J Radiol Open. 2018;5:58-63. doi:10.1016/j.ejro.2018.03.002

31. Cabarrus MC, Westphalen AC. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate—a basic tutorial. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6(3):376-386. doi:10.21037/tau.2017.01.06

32. Asif A, Nathan A, Ng A, et al. Comparing biparametric to multiparametric MRI in the diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancer in biopsy-naive men (PRIME): a prospective, international, multicentre, non-inferiority within-patient, diagnostic yield trial protocol. Urology. 2023;13:e070280. doi:10.1136/%20bmjopen-2022-070280

33. Screening for prostate cancer using biparametric (bp) MRI. Prostate Matters. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://prostatematters.co.uk/screening/screening-for-prostate-cancer-using-biparametric-bp-mri/

34. Lee G, Oto A, Giurcanu M. Prostate MRI: Is Endorectal Coil Necessary?—A Review. Life (Basel). 2022;12(4):569. doi:10.3390/life12040569

35. Almansour H, Afat S, Fritz V, et al. Prospective Image Quality and Lesion Assessment in the Setting of MR-Guided Radiation Therapy of Prostate Cancer on an MR-Linac at 1.5 T: A Comparison to a Standard 3 T MRI. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(7):1533. doi:10.3390/cancers13071533