Osteoporosis affects millions, but most people don't know they’re at risk until it's too late. Fortunately, many of the biggest risk factors are preventable. By understanding what contributes to bone loss and making informed lifestyle choices, you can protect your bones well into later life. In this article, we break down five key risk factors for osteoporosis and what you can do now to avoid them.

Osteoporosis is a health condition leading to weakened bones. Bones become more fragile, and the likelihood of broken bones, such as broken wrists, hips, or spinal bones, increases. Even simple everyday actions, such as a cough or a sneeze, can cause a fractured rib.

The onset of osteoporosis is gradual. It is a “silent disease” – individuals are often unaware they have the condition until a fracture occurs1. Understanding the risk factors and taking proactive action, as well as early diagnosis, are the best measures to keep bones healthy.

Risk Factor 1: Lack of Weight-Bearing Exercise

Why It Matters

Specialised bone-building cells, osteoblasts, grow and strengthen in response to pressure. Regular activity, such as resistance training, therefore keeps them strong. Indeed, physical activity has been shown to improve bone health among older adults and prevent osteoporosis2.

In contrast, lifestyles that are more sedentary have been linked to weaker bones and faster loss of density. In a study of 413,630 participants, sedentary behaviour significantly increased the fracture risk of frail individuals3.

What You Can Do

Incorporate regular exercise. Just 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity can help prevent osteoporosis4. There are a variety of exercise activities that could support better bone health:

- Aerobic exercise: fast walking, jogging, cycling, swimming

- Weight-bearing exercises: running, skipping, dancing, aerobics, jumping

- Resistance exercises: press-ups, weightlifting, using weight equipment at the gym

For those who sit a lot, remember to take regular breaks. Set a reminder to get up every 30 minutes, and incorporate walking meetings into your work routine5.

Risk Factor 2: Poor Nutrition

Why It Matters

A primary component of bone is calcium. Calcium is supplied to the body through diet, and proper absorption is supported by vitamin D. Without these vital minerals and vitamins, bone structures weaken, and bone health diminishes.

It is estimated that adults need 700 mg of calcium per day and 10 µg of vitamin D4. Deficiencies in either of these dietary components increase the risk of bone thinning and fractures6.

What You Can Do

Optimise your diet. Avoid highly processed foods with low nutritional value. Increase the intake of calcium-rich foods and sources of vitamin D4.

Risk Factor 3: Smoking and Excessive Alcohol

Why It Matters

Smoking and excess alcohol consumption can be detrimental to health in several ways, including increasing the risk of osteoporosis.

A meta-analysis pooling data from over 40,000 participants showed that smoking reduced bone mass and increased the risk of bone fracture by 13 per cent in women and 32 per cent in men7.

Smoking can also interfere with oestrogen production, reducing oestrogen levels by up to 50 per cent8. Oestrogen is crucial for bone health, as this hormone inhibits the activity of bone-demolishing cells known as osteoclasts.

Alcohol can similarly diminish bone health. In addition to increasing the risk of falling, alcohol disrupts vitamin D metabolism, reducing the absorption of calcium9,10.

What You Can Do

Modify your lifestyle. Firstly, quit smoking. Seek out stop smoking services available through the NHS, including one-to-one and group sessions and affordable smoking treatments, such as nicotine replacement patches and gum11.

Limit alcohol. The NHS recommends not drinking more than 14 units of alcohol per week. That is the equivalent of six pints of beer or six medium glasses of wine. Where possible, replace alcoholic drinks with non-alcoholic alternatives, such as mocktails.

Risk Factor 4: Hormonal Changes

Why It Matters

Alcohol is not the only reason why oestrogen levels may fall. Hormonal shifts caused by anti-oestrogen tablets, menopause, stress, and nutrient deficiency can also cause a decline in oestrogen.

In their first postmenopausal decade, bone density loss in women is up to 10 per cent12. For men, low testosterone can impact bone health. In a study of 370 men aged 60 and over, 47 per cent with low testosterone had osteoporosis13.

What You Can Do

Speak to your GP about postmenopausal bone health. Hormone therapy, if advised by a healthcare provider, is an option. The risk of bone fractures can be decreased among women who start oestrogen replacement therapy within five years of menopause14.

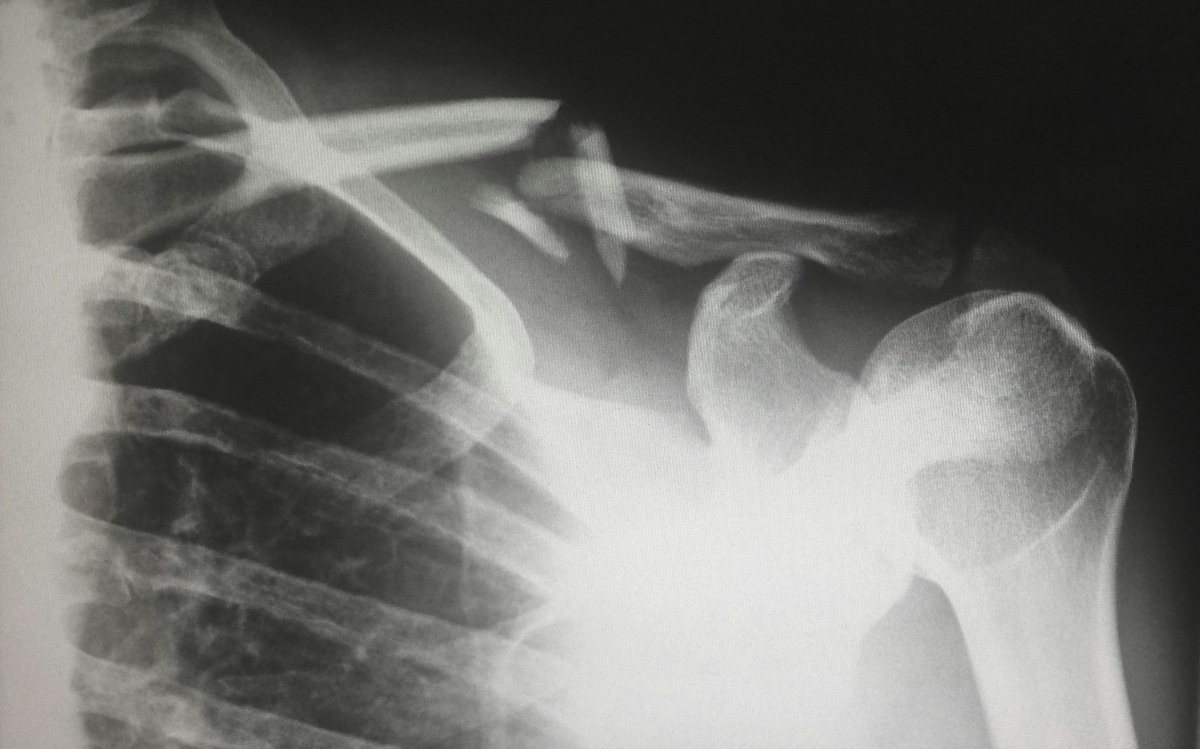

Also consider bone density checks. A bone density scan, known as a DEXA scan, uses X-rays to evaluate bone health15. The amount of X-ray that passes through the bone correlates to bone density. Comparison to a healthy adult assesses whether bone health is compromised.

Risk Factor 5: Family History and Genetics

Why It Matters

Your family history matters. If your parents or siblings have osteoporosis, your risk is much higher. This is because genetics plays a role in bone density and structure. The genes you inherit determine the size and strength of the skeleton.

In studies of twins and families, it has been shown that 50 to 85 per cent of changes in bone density are determined by genetics16.

What You Can Do

A family history of osteoporosis raises risk, but it does not determine your future. There are several ways you can take proactive action and reduce the risk of osteoporosis:

- Know your family history and talk to your doctor

- Consider early screening if you're over 40 and concerned

- If you smoke, quit, and limit alcohol

- Stay proactive with nutrition and regular exercise

Conclusion: Take Control of Your Bone Health

Until a bone fracture, diminished bone health is often symptomless. However, most risk factors for osteoporosis are modifiable, and small changes can have long-term benefits. Commit to regular exercise, ensure adequate nutrition, avoid unhealthy habits such as smoking and excess alcohol consumption, address hormone changes, and be aware of your family history.

Although osteoporosis often progresses without warning, awareness is the first step in preventing fractures and disability. Reflect on your daily habits and make proactive changes to your lifestyle to ensure your bones remain strong and healthy.

Want to keep on top of your well-being? With an Ezra MRI scan, you can proactively assess your overall health. It’s fast, non-invasive, and covers up to 14 organs. Book your scan today and stay ahead of hidden risks.

Understand your risk for cancer with our 5 minute quiz.

Our scan is designed to detect potential cancer early.

References

1. NHS. Osteoporosis. NHS. October 3, 2018. Accessed December 9, 2025. https://nhsuk-cms-fde-prod-uks-dybwftgwcqgsdmfh.a03.azurefd.net/conditions/osteoporosis/

2. Pinheiro MB, Oliveira J, Bauman A, Fairhall N, Kwok W, Sherrington C. Evidence on physical activity and osteoporosis prevention for people aged 65+ years: a systematic review to inform the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):150. doi:10.1186/s12966-020-01040-4

3. Zhou J, Tang R, Wang X, et al. Frailty Status, Sedentary Behaviors, and Risk of Incident Bone Fractures. J Gerontol Ser A. 2024;79(9):glae186. doi:10.1093/gerona/glae186

4. NHS. Osteoporosis - Prevention. NHS. October 3, 2018. Accessed December 9, 2025. https://nhsuk-cms-fde-prod-uks-dybwftgwcqgsdmfh.a03.azurefd.net/conditions/osteoporosis/prevention/

5. NHS. Why we should sit less. NHS. January 25, 2022. Accessed December 9, 2025. https://nhsuk-cms-fde-prod-uks-dybwftgwcqgsdmfh.a03.azurefd.net/live-well/exercise/why-sitting-too-much-is-bad-for-us/

6. Yoon DS, Lee YK, Ha YC, Kim HY. Inadequate Dietary Calcium and Vitamin D Intake in Patients with Osteoporotic Fracture. J Bone Metab. 2016;23(2):55-61. doi:10.11005/jbm.2016.23.2.55

7. Ward KD, Klesges RC. A meta-analysis of the effects of cigarette smoking on bone mineral density. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;68(5):259-270. doi:10.1007/BF02390832

8. Jensen J, Christiansen C, Rødbro P. Cigarette smoking, serum estrogens, and bone loss during hormone-replacement therapy early after menopause. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(16):973-975. doi:10.1056/NEJM198510173131602

9. Bode C, Christian Bode J. Effect of alcohol consumption on the gut. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17(4):575-592. doi:10.1016/S1521-6918(03)00034-9

10. Krawitt EL. Effect of Acute Ethanol Administration on Duodenal Calcium Transport1. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1974;146(2):406-408. doi:10.3181/00379727-146-38115

11. HS. NHS stop smoking services help you quit. NHS. November 24, 2021. Accessed December 9, 2025. https://nhsuk-cms-fde-prod-uks-dybwftgwcqgsdmfh.a03.azurefd.net/live-well/quit-smoking/nhs-stop-smoking-services-help-you-quit/

12. Cauley JA. Estrogen and bone health in men and women. Steroids. 2015;99:11-15. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2014.12.010

13. Mishra AK, Goyal A. Prevalence of Osteoporosis and the Role of Testosterone and Vitamin D Deficiency in Elderly Men: A Cross-Sectional Study. CME J Geriatr Med. 2020;12:39-44. doi:10.61336/cmejgm/2020-12-14

14. Cauley JA, Seeley DG, Ensrud K, et al. Estrogen Replacement Therapy and Fractures in Older Women. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(1):9-16. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-122-1-199501010-00002

15. NHS. Bone density scan (DEXA scan). NHS. October 19, 2017. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://nhsuk-cms-fde-prod-uks-dybwftgwcqgsdmfh.a03.azurefd.net/tests-and-treatments/dexa-scan/

16. Boudin E, Fijalkowski I, Hendrickx G, Van Hul W. Genetic control of bone mass. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;432:3-13. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2015.12.021